By Martin McNamara

Wandsworth Prison_ Summer 1916

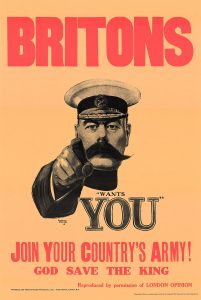

The Easter Rising in Dublin has been quashed. The Great War rages on. A new front is opening up near the River Somme in France and in a Wandsworth prison cell, three ‘traitors to the King’ contemplate their fate. Liam, an Irish Volunteer from the Dublin rising, Alfred, a deserter from the British Army, and Henry, a conscientious objector. What, if anything can they learn from each other?

The Easter Rising in Dublin has been quashed. The Great War rages on. A new front is opening up near the River Somme in France and in a Wandsworth prison cell, three ‘traitors to the King’ contemplate their fate. Liam, an Irish Volunteer from the Dublin rising, Alfred, a deserter from the British Army, and Henry, a conscientious objector. What, if anything can they learn from each other?

Historical Background

The Easter Rising 1916

The Rising was an armed rebellion intended to end British rule in Ireland and establish an independent Republic. It took place in Dublin in 1916 whilst the UK was heavily engaged in World War I. The uprising was crushed after six days of fighting. With many Irish men fighting in British uniforms,

The Rising was initially unpopular with the majority of the Irish population, however public opinion in the country swung behind the rebels after the military authorities in Dublin executed the leaders of the Rising. Many of the republican volunteers came from London including Johnny “Blimey” O’Connor and Sean and Ernie Nunan from Brixton.

The Sankey Committee

In the months after the 1916 Easter Rising, hundreds of captured Irish rebels were moved from Dublin to Wandsworth Prison in south London.

They had been summoned for judgment before the newly formed Sankey Committee, a quickly assembled body tasked with dealing with the large number of prisoners taken during the brief Dublin uprising. It did not take long for the detainees to understand the committee’s true purpose.

The leaders of the Rising had already been executed following the failed insurrection—an action that proved disastrous for the British authorities. Although the rebellion had initially been widely unpopular among ordinary Irish people, the executions in Kilmainham Gaol transformed the leaders into martyrs and ignited a surge of public sympathy for their cause.

Judge John Sankey and his committee hoped the prisoners would claim they had been misled into taking part that Easter Monday, insisting they had no idea their commanders were steering them into such a reckless venture.

But the committee’s hopes were misplaced. Few of the men had any intention of disavowing or betraying their fallen leaders. And so the committee, built to extract surrender, found itself instead confronting a quiet, immovable wall of loyalty.

Conscientious objectors

For the first years of World War One, there was no compulsory military service in Britain. But sustained heavy casualties saw the Military Service Bill pass into law in January 1916 and from March that year, military service was compulsory for all single men in aged 18 to 41, except those who were in jobs essential to the war effort, the sole support of dependents, medically unfit, or ‘those who could show a conscientious objection’ – this was usually interpreted as having strong religious convictions against war, such as being a Quaker. There were about 16,000 of these men.

For the first years of World War One, there was no compulsory military service in Britain. But sustained heavy casualties saw the Military Service Bill pass into law in January 1916 and from March that year, military service was compulsory for all single men in aged 18 to 41, except those who were in jobs essential to the war effort, the sole support of dependents, medically unfit, or ‘those who could show a conscientious objection’ – this was usually interpreted as having strong religious convictions against war, such as being a Quaker. There were about 16,000 of these men.

Irish soldiers in World War One

An estimated 210,000 Irishmen served in the British forces during World War One. The soldiers came from across the religious and political divide of Ireland, both Catholic and Protestant, Nationalist and Unionist. Since there was no conscription in Ireland, about 140,000 of these joined during the war as volunteers. Some 35,000 Irish died. Irish soldiers took part in major engagements at Suvla Bay in Gallipoli and in mainland Europe, including battle of the Somme which took place from July 1st 1916 – November 18th 1916

An estimated 210,000 Irishmen served in the British forces during World War One. The soldiers came from across the religious and political divide of Ireland, both Catholic and Protestant, Nationalist and Unionist. Since there was no conscription in Ireland, about 140,000 of these joined during the war as volunteers. Some 35,000 Irish died. Irish soldiers took part in major engagements at Suvla Bay in Gallipoli and in mainland Europe, including battle of the Somme which took place from July 1st 1916 – November 18th 1916