by Anne Curtis

A week before my first play “Just above Dogs” was performed at the London Irish Centre in Camden, I received an email saying “wasn’t it awful that the portrayal of Irish people in plays was always so negative?” or words to that effect. My correspondent had read a short article in Irish Post promoting the play accompanied a rehearsal photo, which showed two of the actors Kevin Bohan and Kieran Moriarty (Left) fighting.

A week before my first play “Just above Dogs” was performed at the London Irish Centre in Camden, I received an email saying “wasn’t it awful that the portrayal of Irish people in plays was always so negative?” or words to that effect. My correspondent had read a short article in Irish Post promoting the play accompanied a rehearsal photo, which showed two of the actors Kevin Bohan and Kieran Moriarty (Left) fighting.

I never heard from my correspondent again so I presume that they did not bother to come to see the play. Had they, they might have found out that far from being a criticism of the Irish labourer the play is in many ways a tribute to them.

The play opens with the privately educated Cian Carroll accusing his wealthy building contractor father of using sharp practices against the men, including his godfather who worked for him. Dec is unrepentant: “I gave him and many like him work, which in case you haven’t noticed, is more than Ireland gave him.”

The involvement of the Irish workers in the British construction industry began in the eighteenth century when poverty and lack of work in Ireland saw many come over to help build the canals, railways and other early large-scale civil engineering projects. However it was after the end of the Second World War, when soaring levels of unemployment in Ireland and a boom in British construction led to the industry being the largest single employer of Irish migrant labour.

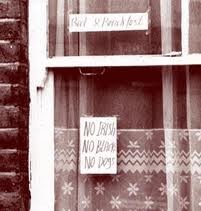

In this almost completely male industry the Irish lived for long periods in digs, onsite in camps and other types of temporary accommodation. They were not always welcome and notices such as these appeared in windows.

In this almost completely male industry the Irish lived for long periods in digs, onsite in camps and other types of temporary accommodation. They were not always welcome and notices such as these appeared in windows.

Their ill-treatment however cannot just be laid at the doors of the English. Mikey and Dec Carroll who come over from West Cork to find work on the sites, have lost before they have even begun. They are duped out of their meagre savings by a fellow Irishman on the boat over. In the second scene we see them outside Camden Town tube station meeting the gangerman who will go on to exploit them. Unscrupulous Gangermen could spot a ‘newbie’ lining up in Camden, north London simply by looking at their boots. New boots were likely to be worn by men who did not know the rules of the game. Easy targets.

Scene Four finds the brothers working on a project away from London in the Nottinghamshire countryside. Dec, considering returning home bemoans the fact that “We’re two fellas with holes in our pockets.” Mikey reminds him that he can’t go home. “Tell me what will they say to a man who comes back from England in shirt sleeves with barely the price of a pint in his hand? “ If you left Ireland to go to England you were supposed to make something of yourself!

Opinions about Irish labourers varies. Stereotypes based on a deep-rooted anti-Irish prejudice were not uncommon, Irish workers often erroneously viewed as living chaotic lives, spending most of their time and money in the pubs. What many forget is that, these men were not allowed to return to their digs during the day leaving them with little choice but to frequent the pubs and occasionally the launderettes to keep themselves away from the cold. As Mikey Caroll says :

“It’s the Sunday afternoons that kill you…when the work stops, when there’s no site, no pub, no fellas to talk to. Just yourself in a room or launderette, listening to time passing, thinking back and wondering what is happening everywhere else. Working all over but belonging nowhere”

I hope that Mikey and Dec Carroll illustrate the dilemma faced by many labourers. Do you abide by the rules or plough your own furrow? How far will you go to better yourself? Is it okay to exploit others even ‘your own?’ What is more important to you- the camaraderie of ‘your own’ or the loneliness of walking out of the pub to make your own success? You make your own decision.

“Where will I find you?” asks Dec of Mikey. “Don’t I drink at the Crown in Cricklewood? replies his brother. That iconic north London pub was for many Irishmen a home from home, a place where you could find work, get your cheque cashed (for a fee) and kill the thirst from the dust of the day. Listen to the music and voices from home. Now the Crown Clayton hotel, its clientele is slightly different but its Irish heart remains the same. It is very kindly allowing us to hold some of our rehearsals there. We are very grateful.

“Where will I find you?” asks Dec of Mikey. “Don’t I drink at the Crown in Cricklewood? replies his brother. That iconic north London pub was for many Irishmen a home from home, a place where you could find work, get your cheque cashed (for a fee) and kill the thirst from the dust of the day. Listen to the music and voices from home. Now the Crown Clayton hotel, its clientele is slightly different but its Irish heart remains the same. It is very kindly allowing us to hold some of our rehearsals there. We are very grateful.

For reasons I can’t understand, no one has thought it appropriate to build a monument to these men, of whom the Scottish contractor William McAlpine is reported to have said “Their (the Irish) contribution to the success of this industry has been immeasurable.”

But Cian Carroll understood. As he says to the old labourer in the hostel: “What about the motorways, the hydroelectric projects, the bridges, the tunnels, the housing estates. Faceless every one of them yet they make this country work – this country would be nothing without what you did?”

Anne Curtis

Click here to listen to Kevin Bohan perform a monologue from the play.