What can a wife do when a husband gambles on his own life? This was the dilemma faced by Muriel MacSwiney when her husband Terence, republican Lord Mayor of Cork, Ireland announced that he was going on hunger strike in protest at the two-year sentence handed down to him, for what he believed were unjust charges in August 1920.

Frustrated that three Irish Home Rule Bills had not reached the statute book, angered by the refusal of the British to recognise the victory of Sinn Fein, the pro-independence party in the post-war General Election of December 1918 and disillusioned that Britain had blocked Ireland’s right to speak at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, the Lord Mayor chose desperate measures. Challenging their validity, he told the court that, it was he, not they who would decide on his sentence. “I shall be free in a month alive or dead”.

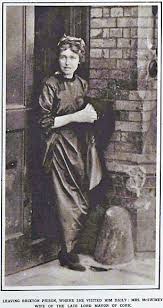

Muriel left her two-year-old daughter with her mother Mary in Cork and headed off to London to support her husband who had been taken to Brixton prison.

With her in-laws: Min, Annie and Peter alongside Art O’Brien of the Irish Self Determination League they sort to challenge the view that MacSwiney was a criminal. They did not succeed, in spite of an impressive campaign that saw the intervention of King George V, the threat by Americans to boycott British goods, strikes and protests in many parts of Europe and beyond. Terence died on 25th October 1920.

Muriel Frances Murphy was born on June 8th 1892, her father was Nicholas Murphy of the brewing family and her mother Mary Gertrude Purcell was the daughter of a regional bank manager. They lived in Carrigmoore, a mansion in the wealthy suburbs of Montenotte on the north side Cork city.

Muriel Frances Murphy was born on June 8th 1892, her father was Nicholas Murphy of the brewing family and her mother Mary Gertrude Purcell was the daughter of a regional bank manager. They lived in Carrigmoore, a mansion in the wealthy suburbs of Montenotte on the north side Cork city.

Although Muriel was raised in very comfortable circumstances, she later recalled that it had been a very lonely childhood, one in which she was deprived of the friendship of other children.

This wouldn’t be surprising. The Murphys’ kept a ‘full staff’ and in Edwardian times it was common for the children of wealthy families to spend more time in the company of their nanny than their parents. Muriel was the youngest of six children by six years, so by the time she was a toddler all her siblings would have been away at school or leading their own lives leaving Muriel with only her nanny and later governess for company. In keeping with the times, she would have ‘visited’ her parents downstairs rather than been with them all the time.

Muriel had three elder sisters: Nora, Mabel and Edith and two elder brothers Nicholas and Norbert. The Murphys, like many wealthy families of the time had a tradition of educating their children in expensive schools in England. The boys went to Ampleforth in Yorkshire whilst the girls went to a convent run by the Sisters of the Holy Child Jesus in London.

Two of Muriel’s sisters became nuns. Nora remained in England entering the convent of the order that she had been at school with. Edith joined the Sisters of Charity in Tramore later becoming Reverend Mother at their school in Wellington Road, Cork. Mabel married her second cousin, James Murphy and went to live in his thirty roomed mansion in the Ring of Mahon. They had a one daughter Dorothy.

As Muriel only attended school, the Convent of the Holy Child Jesus in St Leonards on Sea, Sussex, from the age of fifteen to seventeen we can assume that she was ‘finished’ rather than educated. Muriel regretted her lack of formal education and remarked that she had learnt little of any value whilst at this school.

However, the lack of formal teaching did not hold her back. She appears to be something of a linguist speaking French, German and teaching herself Irish. She played the piano well, drew and painted competently and greatly appreciated art.

Early Adulthood and Radicalisation 1910- 1915

Muriel claimed that she had had a social conscience from a young age admitting that she couldn’t understand why some children were so poor. whilst others like her were well off. Cork would have been a relatively small city at the time. The hills of Montenotte were not far from the slums in the centre, making Cork’s poorer inhabitants easily visible from the window of a passing carriage. Muriel would have had to be ‘blind’ to not to notice the difference between her lifestyle and that of the ‘shoeless’ children playing in the streets.

The Murphys were great philanthropists, donating money for orphanages, hospitals, churches and schools in the city. It does not require a huge leap of faith to imagine what Muriel might have seen when accompanied her family on visits to the places which they had funded.

Muriel left school in about 1910 and there is no record of what she did for the next few years apart from her attendance at a couple of ‘society’ weddings. We can presume that she would have a lifestyle commensurate with a ‘society girl’ of the time: tennis parties, bridge, ‘at homes’, trips overseas including the Grand Tour. We know that she attended music lessons at Mrs Fleischmann where her friendship with fellow pupils Tilly Fleischmann and Geraldine O’Sullivan developed. It was Geraldine who would be with Muriel at key points in her life including the birth of her daughter and Terence’s hunger strike.

Shortly after the outbreak of the First World War in September 1914, Muriel answered a call for volunteer nurses and worked at the South Infirmary in Cork. She didn’t stay long and left when she felt that, in supporting the war, she was part of an ‘imperialist plot’. Muriel’s brother Norbert served in the regiment of the South Irish Horse and saw action in northern France.

Mrs Fleischmann would hold musical recitals at the end of each term in order to give her pupils opportunities to perform. Seemingly, it was at one of these events in the Christmas of 1915 that Muriel met Terence for the first time. One writer said that she ‘engineered’ this meeting having been impressed when she heard him speak at a meeting to commemorate the Manchester Martyrs. The Manchester Martyrs were three Irishmen executed in Manchester 23rd November 1867 for the supposed murder of a policeman, earlier in the year. Many thought that the evidence on which they were convicted was very weak and even incorrect.

It would be wrong to think that Muriel’s interest in Irish nationalism had its roots in her attraction to Terence. There is no doubt that their shared interest provide a context for their relationship to develop but, as her attendance at such a meeting shows, she had an interest in Irish Nationalism long before she met her future husband. This was not uncommon, as she made clear in her testimony to the American Congress in 1920. This is how she described herself at that time:

“I think I am rather characteristic of a certain section in Ireland. The younger people of Ireland have been thinking in a way that some of the older ones have not. There, some years ago the Unionists did not wish an Irish Republic. They wished to belong to England. They were well off and quite comfortable and thought only of themselves. That is dying out now. The younger members of such families are Republican. On account of that, I did not get the opportunity to meet Republicans when I was a child. That was why I was sent to school to England. I am only characteristic of a great many who are brought up shut up at home. And still the Irish spirit comes out of them in spite of everything. So until I was about twenty-two I did not get the opportunity to do very much”

Whilst the cause of Irish nationalism was much more ‘working class’ in Cork a cursory glance at those involved in the Easter Rising in Dublin 1916 reveals the truth of Muriel’s words. Mary Murphy, her mother was an Imperialist and Unionist and Muriel’s habit of bringing nationalist newspapers such as Arthur Griffiths “The Volunteer” into the house would definitely have caused tension. It was through reading such papers that Muriel’s commitment to Irish nationalism increased and she joined the Cork City Branch of Cumann na mBan in 1915. The branch was run by Min MacSwiney, Terence’s elder sister.

Cumann na mBan, the ‘League of Women’, an auxiliary corps, complemented the all-male Irish Volunteer Force (IVF). It was a paramilitary organisation and women were used as messengers, scouts as well as being involved in the movement of funds and weapons, a few even saw action. We know from her own statement that Muriel transported some guns from Dublin to Cork prior to the Easter Rising.

In the arrests that followed the Easter Rising, Muriel played a key role in visiting the men who had been jailed or interned in England. She visited Wandsworth prison in London where Arthur Griffiths and Douglas French Mullen were held and Wakefield prison where Terence was incarcerated.

Beliefs

In common with all her siblings Muriel was baptised Roman Catholic and raised in that faith. However, she admitted to the American Congress in 1920 that, whilst she had nothing against the Church as an institution, she simply ‘did not believe its teaching’. In contrast Terence was a devout Catholic and their correspondence, whilst he was in jail revealed that she attended Mass and went to Confession weekly as a married woman.

In later years Muriel declared herself an atheist. She has been described as being somewhat ‘anti-catholic’ when, according to Angela Clifford, what she really wanted was a secular state where the powers of the Church were rolled back and issues such as housing and social services improved.

Muriel was passionately concerned about the plight of families with large numbers of children without sufficient resources to raise them. She believed birth control should be available to all and was particularly scathing about the Roman Catholic Church’s opposition to its use. Although on occasions she declared her opposition to the Church she was no anti-cleric. In her letters to Angela Clifford she welcomed the election of the potential reformist Pope John XXIII in 1958, spoke approvingly of ‘worker priests’ and the Quakers.

Muriel was motivated by anti-imperialism all her life. In the 1950s and 1960s she supported the rights of small nations such as the Bretons, Algerians and the Vietnamese to break away from their colonial masters. As a Catholic myself I can’t help but think that she would have been very much in favour of Pope Francis and his mission to the poorest in society.

The Married Years 1917- 1920

The Married Years 1917- 1920

As Mrs Murphy refused her consent to the marriage of her daughter to Terence, Muriel had to wait for her 25th birthday in June 1917 when she inherited money from her father, before she could marry. Their wedding was held in Bromyard in Herefordshire where Terence, along with other Republicans was under open arrest, his movements being restricted to within five miles of the village.

Geraldine O’Sullivan, her closest friend from Cork and fellow member of Cumman na Bhan stayed with Muriel in Bromyard from the end of May to her wedding day: “Our landlady was a nice quiet woman, eager to make us comfortable and was not over curious. Like the rest of the people in the district, she seemed to think that the Irish volunteers were sort of ‘cousins’ to the British army where certain members were subject to a kindly disciplinary action. …….They were so happy that day in June with no apparent premonition of the dark times ahead”

Terence was released shortly after the wedding and they were able to return to Ballingeary in West Cork. It seems that those few weeks in Bromyard and the subsequent couple of months were probably the happiest consecutive times that Terence and Muriel spent together.

Terence was released shortly after the wedding and they were able to return to Ballingeary in West Cork. It seems that those few weeks in Bromyard and the subsequent couple of months were probably the happiest consecutive times that Terence and Muriel spent together.

In September, the couple moved to Cork and Terence went back to organising activities for the Irish Volunteers which involved much travelling. He continued to be the subject of police attention. In October 1917, Terence began the first of his ‘post- marriage’ imprisonments when he was sentenced to six months for sedition. In November 1917 he began a hunger strike for better treatment and was released after four days under the ‘Cat and Mouse Act’. * In March 1918 Terence was arrested again and it was while he was in Belfast jail that their daughter Maire was born.

Married life was tough for Muriel as Geraldine O’Sullivan explains:

“Their married life was so short and tormented. Muriel accustomed always to security and ease now showed extraordinary courage and patience. When he left the house, she never knew if she would see him again. He rarely spent the night at home but stayed at carefully selected houses all over the city, a different one each night. He was in and out of jail and on the run during his brief periods of freedom.”

“During one of his spells in jail I went to stay with Muriel so that she would not be alone when the baby was born. This was a very difficult time for them, he consumed with anxiety for his wife and child and she suffering loneliness and worry until the daughter was born.”

In the post-war general election of 1918 Terence was elected unopposed for the outlawed pro Republican party, Sinn Fein whilst he was still in prison. In 1918-19 Muriel became seriously ill with the influenza that raged throughout Europe and Terence was released to be with her. Then, early in 1920 Terence also became a Sinn Fein city councillor. He worked long hours in order to keep up with his civilian and military work.

In March 1920 Tomas MacCurtain, Brigadier Commander of the volunteers for Cork and Lord Mayor of Cork was killed in his home by an Royal Irish Constabulary squad in the middle of the night. It was while the country was still reeling with shock and horror at the murder by the Crown forces of Lord Mayor MacCurtain that Terence, his deputy was elected his successor. Five months later in August 1920 , he was arrested for the last time, in City Hall. Terence immediately began a hunger strike as the ultimate protest against the validity of the British courts in Ireland. He was brought to Brixton prison in south London to serve his sentence.

Hunger Strike August – October 1920

Hunger Strike August – October 1920

Muriel arrived in London twelve days after Terence’s arrest. She was ‘billeted’ at the Jermyn Hotel in Mayfair and took the tram to Brixton daily to visit Terence. The MacSwiney family had organised a rota so that Terence ‘who did not want to be alone’ always had someone with him. Outside those hours Muriel would have assisted with the publicity campaign run by Art O’Brien from the Office of Irish Self Determination League along with Min, Terence’s sister. Muriel who was well informed, personable and photogenic was a key part of this.

It is hard to imagine what it must have been like for Muriel to watch the man she loved die a slow and painful death. Death from a hunger fast involves a lot more than resisting the desire for food. The body has no energy which makes any normal activity such as breathing exhausting and difficult. Bed sores develop when the person has no energy to move and, as the muscles waste, nerves can become inflamed resulting in the painful condition of ‘neuritis’. Most, when in the presence of someone who is ill can usually offer something to either ease their discomfort or assist their recovery but Muriel could only sit and watch. It is to her credit that she managed to ‘hold it all together’ and didn’t collapse until after Terence’s death on October 25th 1920. She was too ill to attend his funeral.

Trip to America- December 1920

Just a few weeks after her husband’s death, Arthur Griffiths, the leader of Sinn Fein told Muriel that he would like her to go to America to publicise the cause. She later admitted that she hadn’t wanted to go and had contacted Arthur to say so. However when he replied with “I urge you to go” she presumed that it was an order and went. As she didn’t want to go alone, she asked Min, Terence’s sister and head of Cumman na Bhan in Cork city to accompany her.

Just a few weeks after her husband’s death, Arthur Griffiths, the leader of Sinn Fein told Muriel that he would like her to go to America to publicise the cause. She later admitted that she hadn’t wanted to go and had contacted Arthur to say so. However when he replied with “I urge you to go” she presumed that it was an order and went. As she didn’t want to go alone, she asked Min, Terence’s sister and head of Cumman na Bhan in Cork city to accompany her.

The SS Celtic carrying Muriel and Min docked in New York in December 1920 and was greeted by thousands. They had gathered in the dockyard since dawn and lined the streets to cheer the newly widowed Muriel and her sister in law Mary MacSwiney to America. One wonders what Muriel must have been feeling at this time. Even so, according to the newspaper reports of the time she was a great ‘hit’ and became the first woman to be awarded the Freedom of New York City.

These days we think a great deal about mental health, but it was less common back then. Imagine what it must have been like for Muriel who had to watch her husband die a slow painful death in a foreign city, and then instead of being given time to recuperate back in Cork was expected to travel thousands of miles away to take part in more activism.

Return to Ireland – Anti Treaty Campaign

Muriel was back in Cork when the Anglo Irish Treaty 1921 which ceded six of the counties of Ulster to the UK was signed, obliterating the dreams of an independent united Ireland. Muriel must have wondered what exactly Terence had died for.

In spite of this Muriel campaigned against the Treaty by taking part in protests and speaking at rallies, as well as cooking for the Volunteer troops at the outbreak of the Civil War which followed the signing. These actions put Muriel outside of the law and one occasion she was arrested.

In September 1922 she was smuggled out of Ireland to France by the anti-treaty side. From there she embarked on a ship for New York so that she could raise support for the anti-treaty position. She addressed large meetings throughout New England and helped to collect funds for the prisoners. Her protest action continued resulting in her being arrested by the US police and spending a short time in prison.

Move to Germany

In December 1923 Muriel took Maire, her daughter who would then have been about five to Germany for a month but decided to stay on after she found a progressive school for Maire to attend. After that she spent a lot of her life on the continent joining the Communist Party of the country she was currently living in.

To Muriel, moving abroad did not mean giving up her political involvement as she considered it her duty to study world events. She seemed to have found love again when she became involved with Pierre Khan, a member of the French Resistance and fellow communist with whom she had a daughter, Alix.

The Kidnap of Maire MacSwiney, their daughter

Muriel has been criticised in some quarters for being ‘uncaring’ towards her child because she did not always have Maire living with her. However, we should judge Muriel by the standards of the day rather than our own. We should remember that Muriel came from that section of society where relations between parents and their offspring were very formal. Muriel was brought up by her nanny and governess. Her brothers were sent abroad to be educated at a very young age so Muriel wouldn’t have thought it anything unusual to send Maire to a progressive boarding school when she was just five years old. Incidentally, this school, the Odenwaldschule, where the children lived in family type houses was the direct opposite from the cold institutions in which her brothers were educated. Maire later recalled being very happy there.

Muriel chose to move Maire back to live with her in Heidelberg in 1927 when she realised that it was only the children of the wealthy who could afford to attend such a school. After a while she boarded Maire with a local doctor and his wife who ran a small pension that enabled children to attend a local school.

A few years later, just as Muriel was about to take Maire back to live with her in Heidelberg that she received another letter from Min MacSwiney asking if Maire could spend a holiday with her in Ireland. Muriel declined because she was unsure if her daughter would be returned to her.

Min and the MacSwiney family desperately wanted to see their niece whom they had not seen for many years. They were also deeply critical that Muriel was raising her child without any religious beliefs. Min felt that Terence would not have wanted this, so in the summer of 1932 Min came over to Germany with a German friend who had a sister living in the Munich area.

The details of what happened next are unclear and will be dependent on whose side of the story you believe but the upshot of all this was that Maire was taken, without Muriel’s consent, and whisked away to Ireland. Here Min MacSwiney applied for and was successful in being awarded the guardianship of the child. Muriel tried and failed to get her back, all those who had been happy for her husband to be sacrificed for the cause ‘fell away’, when she asked them for help and she found herself alone. She was heartbroken and on her own admission became very ill and did not want to live. According to Muriel, the principal reason for her losing custody of her own child, was that she was not raising Maire as a Catholic.

In her autobiography ‘History’s Daughter’, Maire recalls asking her mother on several occasions to be allowed to come and live with her but always being told that this was ‘not possible’. As Maire recalls that they had a warm and loving relationship we know that Muriel did bond with and love her daughter. Having read the varying accounts, I wonder if Muriel’s inability to provide a permanent home for daughter might have had more to do with her illness rather than anything else.

In her autobiography “History’s Child”, Maire explained that her mother suffered from severe depression all her life. Although depression can be brought on by trauma, we should not draw a direct line from Terence’s death to the onset of Muriel’s depression because some sources suggest otherwise. For example, in February 1920, Mary Murphy wrote to Terence asking him to speak to their doctor and to use his influence to stop his wife undergoing the new and experimental ‘electric’ treatment. In 1917 Muriel’s friend, Tilly Fleischman wrote to Muriel thus:

“I cannot tell what a relief your dear letter was to me. I have been terribly worried. Dearest Muriel , no matter how depressed and miserable you feel in the future, do send me a line, just a few words on a card to say you were at least alive.”

Severe depression is a huge burden for anyone to carry so one can understand why, under such circumstances Muriel chose to board her daughter in places where her child would be safe and cared for when she was too ill to cope.

Whatever the real reason was for Maire living apart from her mother in Germany, we can assume that Min MacSwiney felt that she could provide her niece with a stable home and, more importantly raise her in the faith that had been so important to her brother. However, that on its own, did not give her the right to take a child away from her mother without consent.

The Years Post 1932

Although very little is known of how Muriel spent the rest of her days we do know that she continued to have periods of severe depression for which she sought treatment in Paris, Germany and Switzerland. Understandably she moved away from Germany as the Third Reich came to power and she spent some time in France before moving to England for the war years. We know from her letters to Angela Clifford that she went back to live in France in the winter of 1951, that she visited England regularly and occasionally went to Ireland. We also know that although her residencies may have changed her socialist ideals never did.

Muriel makes her last ‘public appearance’ in 1957 through the pages of the Manchester Guardian newspaper when she declared her opposition to the fact that a chapel in the newly rebuilt Roman Catholic cathedral in Southwark was to be dedicated to her husband’s memory (Terence’s body lay overnight in Southwark Cathedral prior to being transported back to Ireland for burial). The fundraising campaign to build this chapel had lent heavily on Terence’s name. Muriel felt that this was wrong because Terence would not have approved of having a chapel named after him. The authorities took little notice of her and the dedication went ahead.

Muriel died on 26 October 1982 in Kent aged ninety. She is buried in Kent.

* The Cat and Mouse Act

The Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill-Health) Act (1913), more commonly known as the ‘Cat and Mouse Act’ dictated that prisoners on hunger strike would be held until the prison medical officer determined their life to be in danger. The prisoner was released, allowed to recuperate, and then re-arrested to serve the remainder of their sentence.