Set in Wandsworth Prison London in 1916. Traitors, Cads and Cowards -tells the story of Liam, an Irish rebel arrested after the Easter Rising in Dublin, who has been brought to London for questioning. He is bunked in with Alfred, a shell-shocked veteran of the trenches up on desertion charges. Their other cell mate is Henry, a conscientious objector, court martialled for refusing his call up papers. Through the action, which takes place over one day we find out whether these three very different ‘Traitors to the King’ find common ground.

In December last year Anne Curtis, artistic director of London Irish theatre company Green Curtain, told me how hundreds of Irish rebels arrested after the Easter Rising were brought to Wandsworth Prison for questioning.

This was not a part of the 1916 rebellion I’d ever heard about before. And I readily agreed with Anne when she suggested it might make the basis of a play.

I’d just finished work on another drama about an Irishman held in Wandsworth Prison. “Your Ever Loving” tells the story of Paul Hill, one of the Guildford Four, who spent 15 years behind bars for terrorist murders he did not commit.

Letters Paul sent his family during those years were donated to the Irish Archive Library at the London Metropolitan University. With the support of Tony Murray, who runs the archive, I was able to use those poignant, angry, funny missives to tell what I believe is an important story. And I found that I liked the discipline that comes with using real life narratives and events and voices to craft a dramatic tale.

When I started researching Traitors, the first thing I realised was how most histories about the men arrested after the Rising concern themselves with the leaders executed in Kilmainham Gaol. Or else they relate to De Valera and the handful of fighters who would go on to create the early governments of the Irish Free State.

There seemed very little about the foot soldiers, the nameless hundreds who left their homes and families in a wild attempt to uproot what was then the most powerful Empire on earth.

I think history is more interesting, and possibly more revealing, if told from the perspective of the people who don’t get their faces on the postage stamps or currency notes.

I was aided no end in my work by Doctor Geoff Bell, Irish writer and historian, who was researching his latest book related to the Irish rebellion. Geoff found a cache of testimonies from volunteers in the archives of the Irish Bureau of Military History.

He generously shared these with me. Scores of these men had been brought to Wandsworth for questioning by the Sankey Committee and their words helped craft this story.

During the course of the Great War, several wings of Wandsworth Prison were given over to military prisoners. In 1916 the wings were kept busy; there were soldiers charged with desertion or criminal activities. That year also saw the introduction of conscription and the Gaol had to find space for conscientious objectors who refused their call up and were court martialled.

I hope our play has something to say about the savagery of conflict and its effects on the often forgotten foot soldiers. But also hopefully about the nature of patriotism and about how the ones labelled cowards or traitors can sometimes be the bravest and noblest because they fight only for what they truly believe.

Special performances on Armistice Day (Fri 11th Nov 2016) and

Remembrance Saturday (12th Nov 2016), both at 8:00pm.

Buy tickets on the door £10/8 concessions.

Venue is: West London Trade Union Club

33-35 High St, Acton, London W3 6ND.

(Unfortunately this venue has stairs and therefore no disabled access).

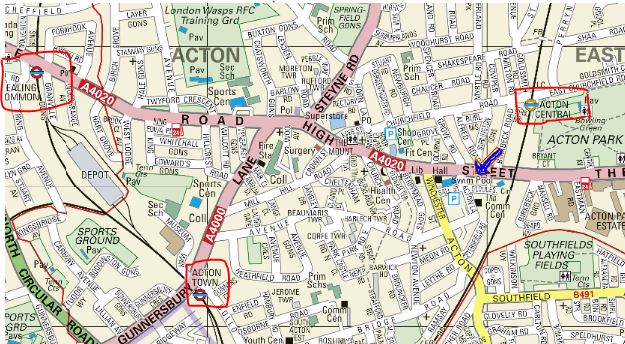

The venue is located in Acton High Street near the junction of Acton Lane and the Vale. It is about a 12 minute walk from Acton Town tube station (District and Piccadilly) and a 7 minute walk from Acton Central on the London Overground. Buses from Shepherd’s Bush and Ealing Common stop outside.

Geoff Bell’s Hesitant Comrades, the Irish Revolution and the British Labour Movement, published by Pluto Press. For more information go to https://goo.gl/F2dfRj

For more on the London Metropolitan University’s ‘Archive of the Irish in Britain’ go to: http://www.archive.londonmet.ac.uk/irishstudiescentre